this is only a test

- Kevin C. Moore

- Jun 18, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 13, 2024

During a recent The Bag Drop recording with the one-and-only Rob Collins, he used the phrase "loose ends" to describe the feeling he desired golfers have when finishing a loop on one of his courses. Two things struck me about this phrase. First, it is beautifully simplistic. Rob captured that the strongest courses in the world draw you back to the first tee in order to chase down something you left out there during the previous round. Whether it be the opportunity to execute a shot you failed at previously or the chance to experiment with different options on how to play a hole, a course's ability to draw you back to it is arguably its most important quality when we consider our favorite places to tee it up.

Second, Rob's phrase and his subsequent points about designing a course to incorporate such a quality underscore that not all things can or should be quantified. With the "loose ends" philosophy of course design, there is no prescriptive approach to creating such a course, nor is there was a way to predictively measure a course's ability to create such a feeling. The "loose ends" philosophy of course design is a phenomenological framing, inseparable from a golfer's experience. And because experience is inherently subjective, developing a predictive measure of a course's ability to evoke a "loose ends" feeling is a fool's errand.

The "loose ends" perspective on course design (or should we call it course design+experience?) is refreshing in today's data-driven, metric-fascinated golf world. Admittedly, I am very much a part of and have contributed to this world. I take great joy in helping golfers work toward their goals through data-driven game improvement efforts. Yet, golf is so complex and layered that I firmly believe it cannot be reduced down to data and analysis of such no matter how advanced our analytical methods become. Any person attempting to reduce golf down to data should think carefully about the inferences their data affords. Doing so requires identifying limitations, alternative explanations, and levels of certainty. As we say in research, good research provides tentative answers, but great research generates richer questions.

A timely and relevant example of reducing golf down to data is the current narrative surrounding the 2023 U.S. Open at LACC. As a member of a golf text thread said, "This isn't really a U.S. Open." The sentiment of this claim and the surrounding conversation? The setup at LACC was not enough of a test for the players. The data for that sentiment? The scores.

What does it test?

Testing or assessment is (for better or worse) a fabric of education. Debates, research, and dialogues around testing are persistent and pervasive. Needless to say, testing is a complex issue with many forms used within education. But regardless of form, when a test is under discussion, the first and foremost question is, "What does it test?"

There is no simple answer to this question, but that is no excuse to avoid the question. When thinking of any test, we must address what it is we are trying to test and what it is that we want that test and an individual's performance on it to tell us. Returning to the U.S. Open, what is it that we want the test to tell us? In my mind, answering that question provides guidance in course choice and setup. It also provides us guidance for how we should interpret the scores (i.e., data) during a U.S. Open.

What is difficult?

For decades the USGA has promoted a test that evokes penal meanings of difficult for the purpose of protecting par. I believe this, although viable and rational, is a narrow and short-sighted conception of difficulty. It is narrow in that it reduces the number of skillsets tested and showcased at the U.S. Open. It is short-sighted in that it quantifies difficulty using the misleading metric of absolute score as it relates to comparing players and U.S. Opens.

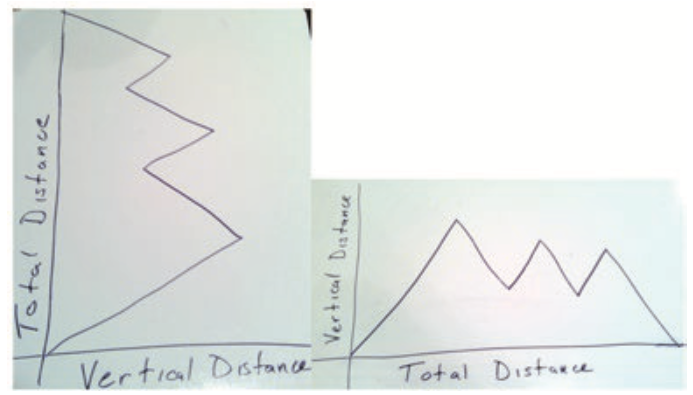

A more productive version of difficulty abandons absolute score and par, replacing it with variance and discernment. A difficult course is a course that affords players the opportunity to separate from the field due to their superior form. Difficulty is a relative construct from this perspective, and one cannot have difficult without having its opposite. Consider two different tournaments and courses as an illustration. With Tournament A, the field shoots +5 to +7 in the first round. With Tournament B, the field shoots -10 to -1 in the first round. Let's assume rather standard distributions of scores across each field. I suspect most people would argue that Tournament A has a more difficult course. They are correct by the typical framing of difficulty, the framing that the USGA has promoted and ingrained in U.S. golf psyche. But, with a relative perspective, Tournament B has the more difficult course. Tournament B afforded a greater absolute score separation of players, suggesting that the course is enabling players with better form to separate from their peers. Said another way, a course becomes more difficult as it becomes more likely that we will see variance in scores based on the form of a player.

To be clear, I do not believe there is some ideal test that the USGA should seek to establish through, for example, a permanent home for the tournament. A course resulting in a desired variance of scores does not imply that it is emphasizing a variety of skillsets. Take Winged Foot as an example. It can certainly be argued that it enabled a single player to differentiate themselves from the field. That's good! But it can also be argued that it enabled such differentiation by emphasizing a particular skillset (i.e., driving).

Emphasizing a particular skillset at a particular tournament is not an issue to me. But, when looking across tournaments, we should be looking for a variety of courses and setup (and technology) that provide both a variance of scores and a variance of emphasized skillsets. These are the ideals the USGA can seek to establish, and in doing so the USGA has the chance to form an identity by showcasing the different types of tests golf can generate. The USGA has the chance to incorporate variety as their identity, ultimately affording a variety of golfers that pass the test and take their place as a U.S. Open Champion.