techucation

- Mar 7, 2023

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 9, 2023

"I’ll propose the phrase didactic object to refer to “a thing to talk about” that is designed with the intention of supporting reflective mathematical discourse."

Two recent events have put technology, and specifically AI tools like ChatGPT, front-and-center in my education life. First, a golf and academy colleague provided a thoughtful framing of plagiarism as it relates to teaching and learning. "Sow the seed of learning and let it reap what it will." Second, Dr. Xiaoming Zhai, a colleague at UGA and a leader in AI use as it relates to Science Education, recently provided a thought-provoking short-form colloquium addressing the affordances and constraints of ChatCPT. Each of these underscored that the place of AI and ChatGPT in education is unavoidable.

You might be expecting a post railing on or supporting the impact of AI and ChatGPT in education. Although an interesting point of conversation, that is not what this post is. This post is an appreciation of technology and its two-parted impact on education. First, technology has affordances. Second, and reflecting Dr. Patrick Thompson's quote above, technology provides us an opportunity to clarify and reflect upon what it is we want students to engage in and learn. Importantly, these two impacts are interrelated and can be mutually supportive.

Technology has many affordances. Technology can support efficiency with respect to cumbersome tasks. Technology can provide tools to create imagery and access impossible without it. Technology can help us inquire into phenomenon, yielding insights beyond our reach without technology.

Consider the calculator, what now seems like a simplistic example technology. One of the many benefits of the calculator is its ability to perform calculations at the so-called push a of button. Similarly, some calculators can create graphs at that same so-called push of a button. Things that used to be computationally or construction complex now seem trivial with the aid of a calculator. And, no doubt, these affordances have major benefits during the learning process, especially via the process of cognitive offloading. But, if not handled appropriately, these affordances can actually be costs.

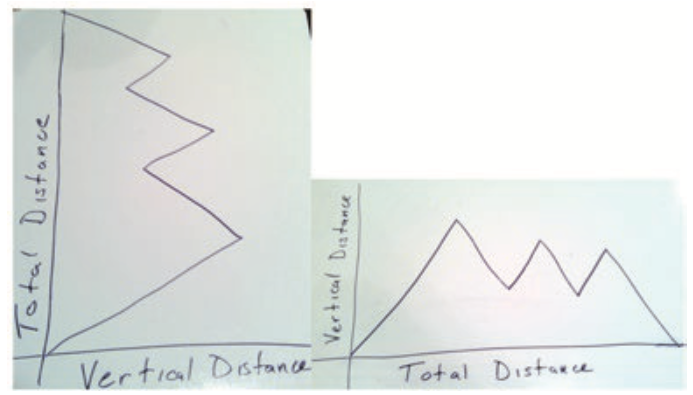

Calculations and graphing are two systems of mental actions central to mathematical thought. Dr. Les Steffe and colleagues have spent a career identifying the uniquely mathematical mental actions involved in constructing number and operations involving number. Similarly, several colleagues have spent much of their careers identifying the uniquely mathematical mental actions involved in constructing graphs. I include numerous students and myself in this group (see Dr. Irma Stevens, Dr. Teo Paoletti, Dr. Halil Tasova, and Dr. Biyao Liang).

Uniquely. Mathematical. Mental. Actions.

Researchers pursuing the aforementioned research programs have emphatically argued that mathematical concepts are constituted by mental actions that come to form mathematical objects through repeated and cyclical processes of enactment, reflection, and abstraction. They argue that these identified mental actions and their transition to mathematical objects must be the purpose of education, or alas mathematics education is missing the mathematics. These mental actions and the associated abstraction of concepts must be intentionally engendered, targeted, and propagated so that students experience a generative and coherent mathematics.

Technology can afford students generative and coherent experiences. Or technology can rob students of such experiences. A calculator could be used at the onset of calculation learning as a tool for performance and answer-getting. Or a calculator could be introduced after particular mental actions are abstracted to stable meanings so that the calculator is viewed as an efficient way to execute calculations while putting the associated mental actions "on hold". A calculator could be used at the onset of graphing learning as a tool for performance and answer-getting. Or a calculator could be introduced after particular mental actions (or in support of particular mental actions and imagery) are abstracted to stable meanings so that the calculator is viewed as an efficient way to produce graphs while putting the associated mental actions "on hold". The former of each robs students of mathematical experience and thought. The latter of each affords students in conceiving technology as a cognitive offloading tool with respect to the complex mental actions and imagery that make up mathematics.

I hope at this point you understand that I perceive technology neither as a good or bad contributor to education. It's all in how we use it. And how we use it requires that we clarify and reflect upon what it is we want students to engage in and learn at the level of mental actions. Only with that figured out can we design and use technology in ways that honor our learning goals. If we do not do so, we run the risk of letting technology take away those key elements of learning, much like technology has robbed many individuals of the joyful process of cooking. What used to be a lengthy bonding process among family and friend units has, in many cases, become an anxious countdown in which we often can't even bring ourselves to wait until the micro-wave reads 00:00.

As a larger point, I wonder the extent our pursuit, use, and proliferation of technology is robbing us from the human condition and experience. Surely, technology is aiding us in doing things faster or more efficiently. Also surely, technology is aiding the speed at which we can produce important outcomes in areas like cancer research or solving issues of famine. But what about other parts of life that have less societal importance and impact? Is producing "more" worth the cost of the process? Take producing a paper outline for a thesis, school paper, research report, etc. ChatGPT can do this! And ChatGPT can do this well in some cases! Regardless of whether or not you believe that a paper outline is a critical aspect of conducting scholarship (I more do than don't), I wonder the extent such a use of technology is removing our engagement with the process of producing things solely for the purpose of producing more things more quickly. And through the continual removing of engaging in the process, are we reducing our ability to enjoy engagement with a process? Is this just another example of becoming a more results-oriented society and looking at each step of the process as a "to-do", rather than the process as a "to-live" part of the journey?

One last point that returns to Dr. Joshua Ralston's motivating post. I refuse to let technology breed actions and attitudes associated with cynicism. AI and ChatGPT's introduction and eventual proliferation provides us an opportunity to reflect on education for the purpose of explicating those things that are critical to the educational process and growth of our students. Such reflective opportunities enable us to revisit and clarify our educational goals so that we are providing students the environment to pursue and achieve their goals in ways that also prepare them to be contributing and critical members of society. Spending time doing so is much more preferred and productive than spending time on efforts driven by cynicism and distrust. I trust my students, and any student that uses AI or ChatGPT to bypass learning is not cheating me, my school, or the academy. They are cheating themselves, and they are cheating the purpose of life. "Sow the seed of learning and let it reap what it will."